GARDEN FRESH: The chips & noodles that launched

a village social enterprise

I heard of the place Guesang from my colleagues at work. However, the first time I saw its name in print was in a pack of banana chips during one of the trade fairs organized for small producers in Baguio during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The name on the pack? Garden Fresh Banana Chips made by Guesang Farmers Organization, Inc. The chips were good – thin and crispy. They had other products like vegetable snacks and noodles, but I opted for the banana chips, being the sweet tooth that I am. The second time I met these chips was during the 2023 Sagada town fiesta. Thus, I got excited when I was given the assignment to visit this Guesang to discover their journey into chips that now has earned them a place in people’s palate. They are known especially for their signature squash chips. If you want to eat Garden Fresh products, come to Sagada, for you may not be able to buy them anywhere as they cannot supply even the local demand.

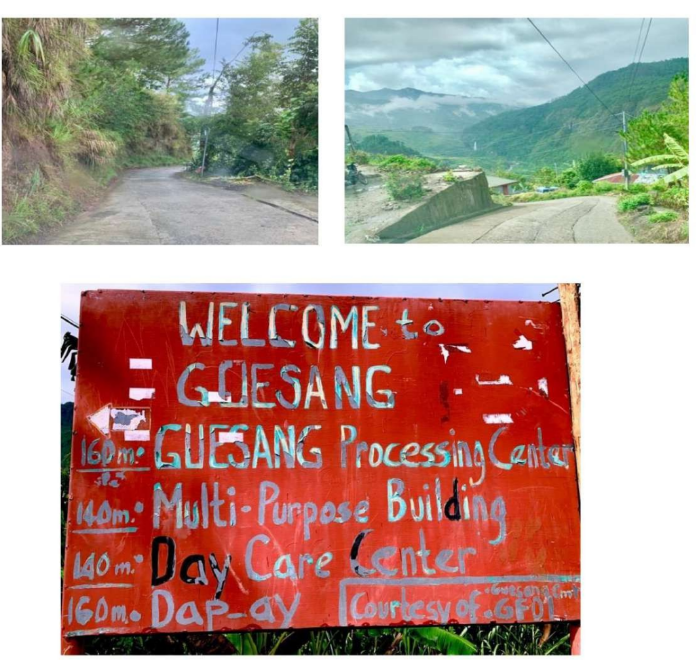

Guesang is a sitio of Bangaan barangay in Sagada, Mountain Province, accessible by motor vehicles from Sagada town center in about 30 minutes by motor vehicle or motorized tricycle (called baja). The access road to the village forks up at Ang-angsa Junction going up Pandayan Mountain along the road going to Bangaan.

A thrilling steep downhill ride will bring you to the upper reaches of the village where you will be welcomed with a sign you cannot miss: against a red paint background is the marker “WELCOME to GUESANG”. It contains information on the distance to four landmarks of the ili (village): Guesang Processing Center, Multi-Purpose Building, Day Care Center, Dap-ay, and in small font, “Courtesy of GFOI”.

So, it is in this hidden village where these processed products are coming from! And you have to walk the e number of meters along a concreted pathway to reach these landmark which are just clustered around each other.

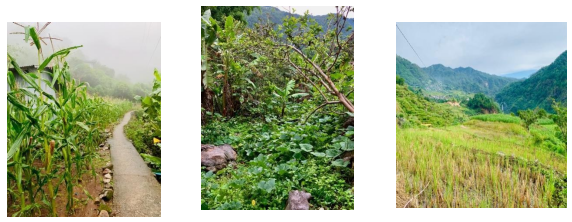

Composed of 53 families in 48 households with a population of 109 individuals, with very slightly more females than males the villagers identify themselves as ePidlisan, a sub-group of the Kankanaey people of western Mountain Province. Surrounded by their rice field and gardens, um-a (either backyard or in the mountains), the villagers are traditionally subsistence farmers cultivating mainly rice, camote, and gabi (taro) their staple food like other village in the Cordillera. However, around the house are bananas, papayas, guavas, citrus of several varieties, and squash, with gardens around the house planted to vegetables.

Some Guesang villagers are also involved in the small-scale mining activities in the nearby barangay of Fedilisan (Pidlisan). Cash income traditionally came from sales of extra farm produce like vegetables, fruits and root crops, and employment in the government service. Some work as tourist guides as Guesang is near the Bomod-ok Falls frequently by tourists.

Home to the Guesang Farmers Organization, Inc. (GFOI), Guesang is not part of Sagada’s traditional tourist circuit. When signals arrived in the neighboring villages, not a beep can reach it. It is really hidden deep down the mountainside of Bangaan that you can only see it fully from the mountains opposite it. The villagers joke that even the barangay forgot they existed and it was only lately that a kagawad position was allocated to them.

However, nowadays, busy motorbikes arrive to pick up packs of noodles and chips. Two entrepreneurs provide access to the internet, and a concrete motor road connects the village to the main road, replacing the steep stone steps that had long been the villager’s access to the main road and the upper villages.

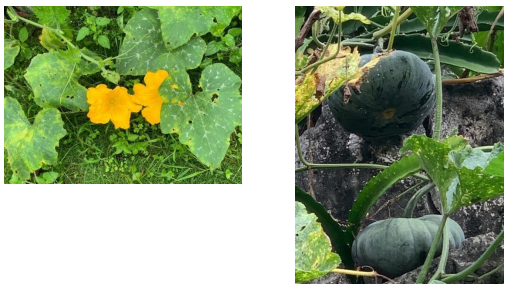

Guesang is endowed with natural resources that allowed people to establish their home there. Located on a narrow shelf at the base of the mountain below the pine forest, it has lands which had been developed into rice fields, camote patches, and residential areas. Like any cold-weather region it only has one rice cropping. However, with grit and industry, the villagers have nurtured these resources sustaining their lives through the traditional diversified and intensive crop production according to the seasons, maximizing the rice fields, yards and forest gardens. Thus, no rice filed or garden was left un-used. Seasonally, they planted beans and corn with the camote in every space possible, even in the crevices of the stone walls Sometimes crop rotation is practiced, with the cultivation of peanuts, squash, and leafy vegetables in rice fields after the rice were harvested. They had a lot of bananas and squash but had no market, or that the access to market was difficult because they had to carry these to the roadside uphill and then wait for a ride to bring it to the Sagada Poblacion market. Along their backyards and forest gardens were sugar cane which traditionally had been the source of sugar before commercial sugar marginalized its cultivation.

GFOI is the dap-ay

The villagers of Guesang did not intend to set up a food processing facility in their hidden village. As a matter of fact, they did not even think of organizing themselves as they are traditionally organized as a dap-ay in the village. The dap-ay is the indigenous socio-political governance institution in many villages in Kankanaey areas in the Mountain Province and parts of the Ilocos, until it was marginalized by the establishment of the State which imposed the present local government system. The dap-ay is now relegated to a disempowered institution which is assigned only in its cultural roles.

In the practice of the dap-ay, community concerns, especially ensuring the well-being of the community, are discussed and acted upon. The agricultural cycle is regulated by the elders of the through rites coordinated by the dap-ay. Some issues are resolved there also, and even petty crimes can be heard and settled. It was the village government. However, this indigenous political structure is not officially recognized as a representative of its constituency unless it registers in one of the government agencies. Since the members of the community belong to the dap-ay, but the dap-ay is not considered a legal entity, matters that need legal representation is assumed by GFOI. Thus, in partnerships with outside parties, like government agencies and non-government organizations (NGOs), the GFOI becomes the representative of the community.

For all intents and purposes, the GFOI is assuming the role of the dap-ay. It is no coincidence because the elders in both GFOI and the dap-ay are the same. The only difference is that the GFOI is composed of men and women compared to the dap-ay which is a council of male elders. By the way, the GFOI leadership is dominated by women. The GFOI coordinates the engagement of the community in development initiatives. As mentioned by Merly Deppas, one of the personalities behind the developments in the village, agencies or organizations who want to contribute to the development of their ili need not organize separate groups since GFOI is already organized and registered with the SEC and legitimately represents the umili (villagers). Some communities have faced problems when each agency which wanted to implement a project in a community would want a signature organization which they can report as an achievement and through which they channel their assitance even if there is already an existing organization in the village. The presence of so many organizations consisting of almost the same membership in one small village can cause conflicting and oftentimes overlapping agenda that in the end may not augur well for the development of the community.

Lately, the GFOI had been encouraged to register as a cooperative, but they want to remain as a an indigenous people’s organization focusing not only on economic matters but the comprehensive development of the village, including their spiritual growth. They believe that they have better autonomy in their decisions as a people’s organization. Complying with the reporting requirements of the SEC is already work in itself and they do not want to be further burdened by the requirements of other agencies. One guiding principle they carry is to not to bite more than they can chew. This stems from their own assessment of their strengths and weaknesses. For them, talking things through substantive collective discussions towards arriving at a consensus (tungtungan), assignment of clear responsibilities and observing/applying the indigeneous values to see things through for the common good guide their decisions. This assertion of their legitimacy as the people’s representative is something other communities can learn from.

GFOI’s emergence as the de facto dap-ay for Guesang shows how the indigenous political structure assigns the responsibility for interacting with the State through an assigned indigenous people’s organization.

Guesang Farmers Organization: the trigger for self-determined development

Journey from Receivers to Givers

According to the elders of the village, Guesang started as an ili with only as few as four households. The villagers fetched their domestic water needs from springs nearby. As population increased, the need for piped-in water also grew, as fetching water competed with time for other tasks needed in a subsistence economy where labor is most crucial. As mentioned earlier, they were invisible to government and they also did not have the agency to bring this to the attention of the government. Since most of the villagers are members of the Episcopal Church and a priest regularly conducts monthly masses at the dap-ay, they came to know that the Church had a Community Based Development Program (CBDP) which was supporting waterworks projects. They submitted their request to the Bishop of their diocese. However, they were not able to reach the priority list before the program ended.

In 2013, Fr. Asterio Dalis was their mission priest. According to Soledad Toyoken, one of the elders in the community, “probably Fr. Dalis saw something in us, how organized and cooperative we are,” and he shared information about the Episcopal Church Action for Renewal and Empowerment (E-CARE) Program that is administered by the E-CARE Foundation.

As a follow-up, an E-CARE staff arrived thereafter to explain that the CBDP has ended and that there is a new one program, the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Program.

The ABCD process refers to the range of activities and exercises that are carried out to engage communities and to identify, appreciate and value local assets and capacities which communities then further enhance and mobilize for sustainable development.

It is a process that enables people to collectively look at “God’s abundance” within their midst – “those assets and resources, often taken for granted, that are found within communities” – and to explore opportunities that such assets can create and/or bring about. It is these identified assets and resources that should then drive the development process.

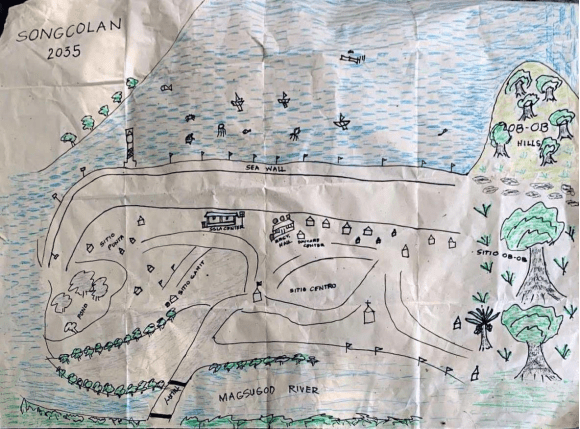

A three-day intensive workshop on ABCD included asset-mapping exercise where the participants took stock of the resources and assets within Guesang, which included identification of gifts of individuals, associations, institutions and connections; transect walks and village-mapping around the community to look at physical resources; and drawing the community asset map. This led to the community visioning exercises involving the exploration of asset-utilization and maximization, conducting of feasibility studies to determine the most viable options and drawing- up of the development vision and plans.

Out of this process, the participants organized themselves as the Guesang Farmers Organization, with their vision, mission, constitution and by-laws, firmed up their organizational structure, and elected their officers. They also required a membership fee and a share capital. It is through this process that the idea of a social enterprise, either individual or as a group, came out. Also, it was suggested that it would be helpful in getting support from government and non-government if they are registered in a government agency. Since all their documents required for registration were already prepared, the organization started the process of registering and the following year, on March 14, 2014, they registered their organization with the Securities and Exchange Commission as Guesang Farmers Organization Inc. (GFOI).

After undertaking a feasibility study on mushroom production, they excitedly submitted a livelihood assistance proposal in 2013 to E-CARE for PhP50 thousand, mostly for individual mushroom production, imagining money literally mushrooming from the spores! Others proposed to improve their farms and gardens. They were granted the funds in June that year under the Receivers to Givers Policy (R2G), interest-free for 12 months. Under the R2G, the livelihood assistance requires that GFOI (the receiver) “grants it back” (the fund it received) to another group, community or association or to itself for another development purpose, thus becoming a giver.

E-CARE facilitated a training on this enterprise and that started their foray into the world of capitalism. But the roads in this world is not smooth. Within three months into their endeavor, they realized that cash was not mushrooming! As a matter of fact, the volume of mushrooms that were colonizing was blah! The temperature at their production sites cannot be controlled which is crucial to mushroom production, the substrates which can be prepared from banana leaves or rice straw were not available. De-leafing bananas led to the death plants and rice straw was not available. Apart from these, there was no assured market. The costs were also rather high compared to other crops which means that the prices have to be commensurate but this means that their mushroom cannot be afforded by many consumers. There was no ready sustained market within their reach which could absorb their production. To top it all, the mushrooms are fragile and have short shelf life thus requiring certain packing materials and timing to market them.

Realizing that six months has passed and they have only about 6 months to go before paying back E-CARE, the mushroom producers shifted their enterprise to chicken egg production. Again, they

Imagined cash laying in their poultry cages. After a few trials they realized that PhP50 thousand is not enough to cover costs until layers give them the cash, uhmm, eggs. Undeterred, and after a member agreed to return their investment and take over the egg production, the group paid back E-CARE and the following year, requested a grant back of PhP200 thousand, shifting their business to buy-and-sell of broiler culls (B-cull).

The B-cull business was a better-studied decision as they observed the big demand for meat among the miners and other workers in the booming small-scale mines in nearby Pidlisan. With this venture, they were able to make some profit and pay back the assistance to E-CARE. With the increasing wealth from small-scale mining, other businesses were booming along the road and areas near the mines, including the selling of B-cull, creating a direct competition to their businesses.

All the time, each member had a specific interest on prospering a livelihood. However, each lacked the capital to start up their individual economic ventures. Although some of them are members of cooperatives, they still found it challenging to access funds in these entities. For one, there are several requirements they have to meet, the interest is pre-deducted and the schedule of amortization does not suit their seasonal income from their intended projects.

The members’ investments were only in their homes, education for their children, pigs for rituals, but none for a sustainable economic investment. After paying back E-CARE in 2018, they decided to again grant back to themselves P500 thousand to fund other livelihood initiatives.

Compared to legal and illegal sources of credit, the R2G has friendly terms. The R2G requires partners who have already received livelihood assistance to offer an incremental amount of the fund received when they grant it back. This is called the add-on gift or simply add-on. It is 1.5% per month of the fund received. One-third of this add-on is returned to the partner, like a rebate, to build their capital so that in the long-term they will become the lenders themselves. Additionally, the add-on is not pre-deducted, and they are allowed to formulate their own internal policies to govern payments as long as they pay back to E-CARE on the due date.

Once it became an E-CARE partner, GFOI started two economic projects: micro financing and food processing. Under the R2G Policy, they used their member’s share capital and their share from the add-on in the micro lending activity. Individuals earn dividends from the micro lending activity through their personal capital share. The micro financing provides easy access to loans which the members use to capitalize their own economic activities, buy farm tools and equipment, spend for the education of their children, for spend for emergency cases. It also provides income for members earned through their share capital. They can use some of the earnings of the fund for community development projects, especially for schools, the church and other community needs. They provision of financial assistance for their bereaved members though their mortuary assistance fund, and give donations for private groups or individuals who request or solicit for help.

Mobilizing towards community development

All throughout this economic empowerment journey, GFOI continued to lead the community towards community development.

Part of the ABCD framework is asset-building, not only in tangible assets, but more importantly in the mindset of partners, or in enhancing/ rediscovering/ renewing/rejuvenating what they have. These interventions focus on values formation, gender-sensitivity, health and environment, to set the enabling framework towards sustainable development. The ECP’s 5th Mark of Mission directs the Church to strive to safeguard the integrity of creation and sustain and renew the life of the earth. In line with this, E-CARE staff conduct an orientation on environmental stewardship, focusing on the current state of the environment, the effects of global warming and climate change and the urgent need to protect the environment from further destruction in every community project. A concrete demonstration of this is the environmental awareness workshops conducted by the E-CARE staff with the GFOI where the concept of carbon offset was discussed. When it can came to the “What can we do” part, the villagers declared “Nalawa nan ili ay mamulaan, maid laeng maimula” (Our territory is wide but we do not have something to plant). Their ancestral domain is wide and for that, they need a lot of planting materials. This is when E-CARE suggested that they can approach Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

Serendipity! At that time, the DENR was implementing the Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project (INREMP) funded by the Asian Development Bank and its Mountain Province office was ready with the planting materials. Thus, in 2016, GPOI mobilized the villagers to restore and rehabilitate 5 hectares of balding forest areas with wildlings, reforest 2.5 hectares of open space by planting forest tree seedlings, and planting 39 hectares of forestlands, forest and home gardens mostly with alnus underneath of which were coffee seedlings. This project is required them to maintain these areas and in 2018, GFOI earned the award as the most performing partner of the INREMP in Mountain Province by the Cordillera office of the DENR. In the same year, GFOI received Php 300,000.00 from the Livelihood Enhancement Support fund under the same program for its community-based banana processing project which it used to construct the Guesang Multipurpose Center, using part of the ground floor to start up their banana- chip production. The following year, the DENR also gave it the best performer award in organizational management.

In 2017, GFOI participated in the construction of a 1,447-linear footpath traversing their sitio to the main road which benefits constituents of nearby sitios and barangays. This was funded through the government’s poverty-alleviation program Kapit-Bisig Laban sa Kahirapan–Comprehensive and Integrated Delivery of Social Services (Kalahi-CIDSS) through the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). The footpath was turned over to Bangaan barangay but its care and overall maintenance was given to GFOI, earning Bangaan the accolade among the 477 barangays implementing the DSWD Kalahi-CIDSS that it is one of those with good record in the overall implementation of the program.

The chip and noodle story

GFOI used the E-CARE livelihood assistance funds it received in several cycles to finance the micro-enterprises of its members. Some spent their allocation to capitalize some businesses like hog-raising, buy-and-sell of goods. Most of them used it to start their production of banana chips using their abundant banana produce. Alongside this was muscovado production. Seeing this in their proposal, E-CARE linked them with the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) for training

to ensure the quality of their products and also to capacitate them in business management. In August 2020, they trained in making peanut brittle, noodles and chips. For the noodles and chips, they looked at their assets and experimented with various vegetable mixes like squash, pechay, amplaya, carrots, and other vegetables in season. Surprisingly, their noodles caught the market’s interest and has become their best seller, even reaching Baguio City and orders from beyond the region. They branded their food products as Garden Fresh which comes as banana chips, squash noodles, squash chips, onion chips, and more. Just look for the Garden Fresh brand. GFOI registered in 16 March 2023 as food manufacturer with the Food and Drug Administration.

Local consumers were the first customers but with E-CARE and DTI, some of their products reached Baguio and Metro Manila. With the easing of pandemic biosafety protocols, 2022 saw a better year for the Garden Fresh products as Sagada eateries increasingly sourced their noodles and chips from GFOI, assured of the freshness of the products. ECARE and individuals carrying the brand participated in trade fairs in Baguio City and during the Sagada town fiestas. The Metro Manila market was also reached through the E-CARE Shop at the compound of the Cathedral of St. Mary & St. John. Their banana and vegetable chips and noodles saw a booming demand, especially at the local market in Sagada. The provincial, regional and national agri-trade fairs also served as marketing exposure opportunities which greatly helped in drumming up demand for the GFOI products. They also tried producing wines from local fruits and banana vinegar.

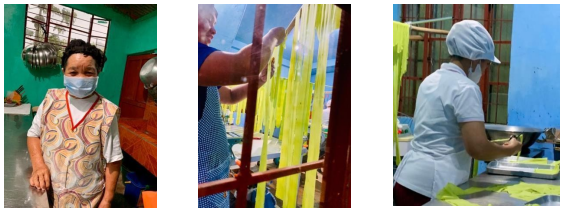

With the increasing demand for Garden Fresh products, a bigger space and better facilities was needed to up their production capacity. Earlier, during their training with DTI, they were informed that the latter can provide the machinery and equipment to improve their productivity and efficiency through better access to technology if they can have a structure to house them. With the community offering a communal space for the put up of their own structure, the GFOI sought help from the Department of Agriculture for a a building. All these efforts, with the help of the E-CARE staff, the Guesang Processing Center or what the DTI calls the Shared Service Facility (SSF), came into being in early 2022. From the ground floor of the multipurpose building, the processors graduated to their own building with more complete facilities. The expanded space and modern equipment allowed them bigger production capacity, higher demand for the local ingredients, better quality control, and the employment of more processors. The management of the SSF is under the leadership of Sheila Patong, Processing Manager. Later in 2022, for their dedication and passion as social entrepreneurs, the DTI recognized them as the most successful service facilities project for the Cordillera Administrative Region.

Marketing Garden Fresh products is by word of mouth but they also maintain a social media account as Guesang Farmers Organizations Incorporation. Some members use their personal social media accounts also promote Garden Fresh products. As member-vlogger @Maderno Baderno, whose viral post of him delivering the products in g-string, opines, “at this point in time that the supply cannot even meet the demand, aggressive promotion could strain the capacity of the processing center, and in the end, would not be able to meet market demands and thus, negatively impact on our integrity.” Again, the GFOI would only bite what it can chew.

As the women became more adept at their trade and skills, they experimented and innovated using more available ingredients in their backyards and gardens.

As of date, they have developed the thin sweetish squash chips, the new darling of the market, something they want to be known for. Another new flavor is green onions with a tinge of chili, an appetizing green chip. Green onions and chili are being planted in containers and gardens in the yards. Probably the neglected um-a and rice fields will bloom with chilis and onions.

The demand for their noodles and chips is high that they cannot even meet the demand from eateries in Sagada Poblacion which serves mainly the tourist population. GFOI is waiting for the assistance from the Department of Agriculture to expand the food processing facility. Because of space limitations, they cannot accept more orders than they can meet. They have the human resources, the ingredients, and the management skills to undergo expansion. One order came at 3:00pm for squash and onion chips to be delivered the following day. Three processors worked immediately until midnight to meet the order which was picked up early morning the following day.

GFOI wants to remind consumers of their products, especially the squash noodles and chips that squash comes in different colors, from light yellow to dark orange. The slight differences in colors in the packs are not due to age. Remember, these products are flying off the shelves and at peak times the processing center has to have 3 shifts just to meet the demand. Color differences are due to the variety of squash used. Do not worry, almost all all ingredients are locally sourced fresh from the garden. There are a lot of similar products in the market, but always look for Garden Fresh by the Guesang Farmers Organization, Inc. Garden Fresh can become an icon of Sagada too with the tagline: “Only in Sagada, Garden Fresh chips and noodles!” As the members would say, “It is best when it’s fresh!”

Income is more than cash

The Guesang Food Processing Center (GPC) has become the main employer in the village. When in Guesang, “Center” refers to the GPC, literally at the center of the village and the hub of economic activity. As many as 18 women take turns in turning the ingredients into chips and noodles. At any time, at least three women are working at the Center. Their food processing business started at one section of the ground floor of their multipurpose building as the kitchen while the other half is the daycare center. When the FFS was built just a few meters away, they moved the processing there.

The processing team is an all-women group, mostly young mothers. But there is also a grandma. They are paid by the hour, a very convenient arrangement for the moms who have to bring to and fetch back their daycare kids from the nearby daycare center where the moms originally used one part as their processing center.

Need to go check on your rice field first? gather the corn? go to the Poblacion? attend a meeting? It is okay. Come when you have the time.

You cannot be a processor? Be a supplier. Bring your squash, bananas, onions, chili to the Center.

You are in school? Plant onions. Sell the chips. Take orders.

A grandmother opined that before, young mothers would often be borrowing for their children or home needs. Nowadays, they are earning income, the ones who run the facility and the organization. And the ones who can now buy goods online. As a matter of fact, two of the processors stopped working as tourist guides. Being near home, not exposed to the elements, and can monitor their children is the choice they have made. Another has a stall in Baguio and during her frequent trips back to Guesang to her frequent trips back to Guesang to visit or to get the Garden Fresh products, she found that being at the center of the production, and not on the distribution side, was more exciting. She decided to turn over her Baguio business to a daughter and return home and be a processor.

How much does one earn as a processor? The rates are decided by the processors themselves with the management after a thorough discussion and arrived at by consensus. They can earn as much as P60/hour which translate into a rate of PhP640 for an 8-hour working day. This is above the PhP470 minimum wage rate for the Cordillera Administrative Region as of December 2024.

Improved economic independence for young mothers can be seen from the decreased number of micro lending borrowers in 2024. A more thorough study may show interesting results. However, this micro lending is giving them investments through their dividends on their share capital. Sometimes they group themselves into small ug-ugbo groups where they pool their dividends. Sometimes they do internal borrowing especially when their due dates for pay back arrives. This is how they practice their ug-ugbo in financial matters, in how they ensure that their group integrity is maintained.

However, it is not only the Guesang villagers who are benefitting economically from this village enterprise. It extends beyond the Guesang community. GFOI makes it a priority to source raw materials for its food processing needs from neighboring villages. In doing so, it helps these communities market their products and encourages them to sustain and improve their farming practices, particularly for squash, onions, and chili peppers. This area of the municipality is especially known for its abundant squash production.

By providing a reliable market for their crops, GFOI not only secures its supply but also influences the cropping decisions of nearby farmers. During peak production periods when local supply falls short, squash is sourced from kakailyan (villagemates) in other areas, such as Belance, Nueva Vizcaya. However, since not all squash are of the same quality, strict quality control is observed when purchasing this key ingredient.

Finding that it is better to be inside the facility and keeping their hands busy, some women have stopped their job as tour guides, a seasonal job. Many processors are now able to work and still attend to their daycare children without being distracted. One had a profitable wagwag (2nd -hand clothes) business in Manila but she stopped and came home to work as a processor and now the president of GFOI. The women find it more fulfilling and practical helping out in the processing center, “adi ka pay maibilag sin agew wenno mabasa isnan udan” (you are not under the heat of the sun or drench under the rain).

Students are learning entrepreneurial skills by selling the products in their own school and outside and getting orders. They also learn to cultivate green onions (scallions) and other vegetables, even in pots, and help in the facility during vacation, weekends, or holidays, preparing the vegetables.

The mom-friendly arrangement at the processing center allows mothers and grandmas to spend quality time with their growing children and grandchildren since they processing center is within the vicinity of their homes. But also, they have quality time with their peers amidst the socialized working set-up at the processing center. The socialization within the Center are venues for learning, advice, info-sharing, problem-solving sessions and just friendly chats.

For the women, their economic independence allows them to indulge in, not only needs, but also wants. Surely, they want beauty products too.

Knowledge and skills

When asked what was the situation in 2013, one response was: No knowledge on documentation and record keeping. The training given by E-CARE and the different line agencies and other organizations have contributed to the knowledge and skills pool of the community. Financial literacy is important in running their social enterprise but this is also applied at home. Although it is individuals who are trained, the sharing of financial reports and their interpretation during meetings are also collective learning experiences. The knowledge and skills learned by the processors, for instance, on current and good manufacturing practices can be applied in their personal lives.

Spiritual growth

One woman wrote that before 2013, before they came to know E-CARE, “Maid usto is pagmisaan” (no regular place for worship). The villagers offered the dap-ay as their for the ECP Christian services. It is also the seat of the traditional governance of the ili. The dap-ay is a small structure and thus cannot accommodate all the congregants. However, it is interesting to note that the dap- ay is also an spiritual center where rituals are performed where all the necessary prayers and propitiations made. Sermons are also delivered to those who violate customary laws and norms. It is symbolic that an indigenous sacred place became the temporary home for Christian worship. It is indicative of the generosity of spirit ingrained in Igorot spirituality and the ECP for the share use of this sacred site. In the world view of the Igorot, it is not lawa (taboo), when it is for the communal good and well-being.

Under the R2G Policy, aside from the rebate to the organization, another 1/3 of the add-on is allocated for the host Episcopal congregation as a contribution to the church’s endowment fund. At that time, the St. Elizabeth congregation was fund-raising for their church building to graduate them from the dap-ay. They requested then from their diocesan bishop if they can use the accumulated 1/3 share of the church to build the church building. They were granted their request and they used this as their contribution to the construction of the St. Elizabeth of Hungary Episcopal Church building which is expected to be functional before the end of 2025. GFOI also pledges annually to St. Elizabeth as an expression of its spiritual stewardship. In building their church structure, the GFOI members led the congregants in providing volunteer labor, food and other needs that they are able to provide.

Indigenous Values at the Core of Sustainability

Binnadang

This term would be best expressed as shared responsibility, although generally it is used to refer to helping one another. This is ingrained in the many communities when the survival of the collective must be ensured. Among the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera, this term is often heard when asked how groups or communities deal with challenges. To GFOI, this is the overarching value that underpins their vision of providing opportunities for farmers to develop and enjoy their resources and potentials towards a sustainable environment. The other core values of galatis and ug-ugbo contain the elements of binnadang, as the collective (whether a group or community or organisation) share responsibility to achieve a task, mission or goal; to exploring solutions and acting together on collective decision. Binnadang thus carries with it the sense of individual responsibility, participation, and solidarity (urnos). One elder opined that the success

of their organization is due to their urnos, saying that one has to study/reflect well on matters, ideas, actions, in order to understand and build solidarity. “Know your capacity to know what to contribute,” according to Mary Badongen, another elder in the community, followed by her advice “waday mangikkan si biang na,” for each one to do and exercise their responsibility.

Ug-Ugbo

The survival of one is the survival of the collective. This underlies the principle of mutual self- help, ug-ugbo, that has long been practiced in many indigenous communities. It concretely demonstrates the value of caring and sharing. In order to survive as a people, as a village, as a group, the collective must care for individual and the individual must share in the burden of collectively resolving challenges and ensuring collective well-being.

Guesang village retains the ug-ugbo culture. Traditionally, ug-ugbo referred to the labor exchange which was practiced during certain phases of the agricultural cycle when intensive labor was needed to finish certain tasks within the season. It was also practiced during rice-field construction. Arable land in western Mountain Province where Guesang is located is very limited because of its mountainous steep terrains. Rice fields and camote patches then are small in area, even 5 sq. m. would be a good size but this entailed a lot of work to level the terrain, stonewall the sides and construct the irrigation canal to the field.

Labor exchange is usually practiced during rice land preparation, planting and harvest periods when labor demand is high and these tasks have to finished on time. Because rice and camote cultivation are individual family affairs, finishing these tasks on time with the season would be challenging. Thus, the practice of ug-ugbo arose to address this need. An ug-ugbo group would work in a member’s field and then go to the next member, serially. For farm activities, these are temporary groups good for one cycle. As society developed and other tasks and needs emerged, this practice became applied to other fields: commercial vegetable production, finances, and community projects, among others.

Cash is needed to pay education and medical needs, taxes, permits, and other basic needs, including construction materials for homes. Ironically, this shift in livelihoods has led to the abandonment of many rice fields and camote patches to weeds. Farming these lands is so labor-intensive and returns are not immediately available, that it is mostly for the love of homegrown rice and other crops that the families maintain their rice fields and camote patches. Some have turned their properties into coffee plantations, a preferred cash crop as they are low-maintenance once they bear berries.

Ug-ugbo has now entered the financial sector with individuals grouping themselves as ug-ugbo. Among the members of GFOI, especially among the women, there are several groups who may have interlocking members, who use their earnings from dividends on their share capital to pool these together into a paluwagan fund that is revolves around the members. Some of them use this to pay back their share of the E-CARE funds. This is actually savings because the member sets aside a part of or the full amount of her share to put into the pool, thus when her turn comes, she gets back all that she has put into the pool for that particular cycle.

Galatis

Galatis is derived from the word “gratis” and refers to voluntary labor which usually happens when there is a community or communal project that has to be implemented. In the construction of the footpaths in the village in 2017, the counterpart of the village was galatis. For the ongoing construction of their church building, labor is also galatis. Galatis is not only labor, it is community mobilization which strengthens their solidarity and cooperation. Management of galatis groups is also a skill since work gangs usually are assigned for specific tasks like food preparation, and if takes days, work division will have to be worked out, implemented and supervised. Galatis can take days, especially for construction projects, and for the footpath project, balancing individual livelihoods with the galatis work resulted to three group working separately in three sites. Specific work in the farm and in the construction site were listed, identifying what can be done by men or women, after which a work schedule was prepared and implemented. Such efficiency shaved off 20 days of the 60-day target.

Kuya

Kuya, no this is not your Tagalog brother. In western Mountain Province parlance, this refers to the act of surrendering a thing, a privilege or opportunity for somebody else or for the common good; donation. It is best expressed as a verb: “Inkuya da nan lote para isnan simbahan” (They donated the lot for the church). The community’s donation of the communal lot for the put-up of the SSF or Guesang Processing Center is a form of collective kuya. The donation of the lot for the construction of the Episcopal Church is kuya. To pass on one’s turn in an ug-ugbo to another who is more in need would be kuya.

Ayyew

Ayyew would be best expressed as “waste not” and this would be the best equivalent of the waste management. This is the center of the asset-based community development framework. This practice is best demonstrated in the how the camote was traditionally used. The root was food for people and pigs, with the pigs getting very small-sized roots and peelings together with the vines and leaves. Anything that did not serve these purposes were plowed under the soil to compost as fertilizer. Kitchen waste was always for the pigs and dogs. With the introduction of feeds, the practice of feeding camote to pigs is now almost gone. Traditionally, every household had a pig pen where all the waste that cannot be used as food for humans and animals were dumped in the pigpen to compost. This compost was later as fertilizer for the rice fields and gardens. Thus, the excess bananas and squash would have been good food for the pigs but the labor required to prepare these as pig feed is tedious. Also, the breeds nowadays cannot just subsist on organic food in order to grow optimally. Pig raising has also waned as livelihood as seen in the many abandoned or unused pigpens in Guesang and in many parts of the Cordillera. Some of the GFOI members went into pig-raising but the infection from the African Swine Fever virus did not help for this livelihood to prosper. Thus, this initiative of the GFOI women to go into food processing is saving their squash and bananas from going to waste, “ta ayyew’ (so it wouldn’t be wasted)! From the asset-based development framework, the neglected rice fields and camote patches or forest gardens are idle and are waiting for willing hands to cultivate them ta ay-yew.

Inayan

Inayan can be understood as the principle of “do no harm.” It forbids doing or bringing harm to people, sacred places or creation, and includes prohibitions against oppressing the vulnerable –

Such as downtrodden, the orphans, the widows, and people in difficult circumstances. It also extend to denying food, drink and/ or shelter to the needy. Even wasting food is considered inayan. The village has embraced non-Igorots – men who have come for work at the small-scale mines and later brought in their families – integrating some of the wives into the workforce at the processing center. These persons have become productive valued members of the community. Providing them with work reflects the principle of inayan – “inayan di adi mangpainum is na-ewew” (it is taboo/ unthinkable refuse to provide for those who thirst). This cultural values ensures that no one is left behind. Surely, before the SDGs were articulated, the Igorots already practiced these principles, living a life rooted in responding to human need through loving service.

Beyond the elders, noodles and chips

Guesang Farmers Organizations, now in its second decade is led primarily by senior members but the responsible officers are young women. Its financial assets are increasing yearly. Individual and organizational assets are accumulating. When asked about their concerns for the organization’s future, they shared that while most of their children and grandchildren are working elsewhere, they remain hopeful that some will return— not necessarily to farm, but to manage the social enterprises that sustain their investments. They also hope the youth will recognize the value of these efforts. For instance, coffee seedlings planted years ago are now bearing berries, raising the question of how these will be processed. The elders believe that engaging the younger is essential, with social enterprises serving as a bridge to attract them and highlight the worth of their heritage and investments. To strengthen self-reliance and support the village enterprise, they may need to restore neglected rice fields and gardens and cultivate more essential ingredients. To stay competitive, they must focus on continuous innovation, market development, and production efficiency. Ensuring human resource continuity remains a major concern, with hopes centered on the younger generation to sustain and grow these initiatives.

Written by: Ms. Bernice Aquino-See, volunteer consultant for E-CARE

When little brings happiness:

Women know what they can do best

Seashores conjure fishers’ boats lining the shores busy unloading their catch on containers being held out by women. For the members of the Seashore Songcolan Livelihood Association (SSLA), the choice of the name of their organization has been deliberate. They are an all-women group from fisher folk families of barangay Songcolan in Batan, Aklan province, whose husbands are subsistence fishers, and no, they do not line up on the shores. They are up and about doing their own thing. Sure, they do actually help their fisher husbands by getting some resources to support the fishing. They did and do – they bought sturdier bangka (small boat) and timing (fish cages), motor to power the bangka, nets and supplies for their husbands’ baon (bring along meal) to the sea.

However, they do more than that. They are tending their baraca (sari-sari store), buying and selling the firshers’ catch, preparing daing (marinated bangus or milkfish) for the market, cooking snacks and going around the village to sell these, all on top of tending to children or grandchildren, sick relatives, preparing meals, and most of all, making sure that when the rains come, they are at the fetching station to fill their buckets with water from the rain catchment facility, otherwise, they wait for the water delivery to come.

Songcolan is a barangay of Batan in the western part of the province of Aklan. It is accessible from provincial capital town of Kalibo via a motor road which takes about 45 minutes through paved roads, or by taking the ferry boat service at the Dumaguit port to Batan port at the Poblacion, considered the oldest port in Aklan, and then take a tricycle to the barangay. Batan was originally called Batang and one of the first areas to be colonized by the Spaniards, and famously associated with Datu Kalantiaw.

Poverty amidst nature’s wealth

Roxas City, the capital of the nearby province of Capiz, sources most of its fish and crabs from Songcolan which they claim to be of better quality, and prides itself as the Seafood Capital of the Philippines. The Songcolan fishers joke that that title. They provide the catch for a variety of fishes, crabs, shrimps, squid, oysters, and other marine products.

Masugod River, actually an estuary, defines the boundary of the barangay Mandong with Songoclan. Masugod River is a lifeline of the Songcolan villagers and other nearby villages. Some fish cages are built within the estuary where they also raise oysters. It abounds in gulaman bato (commonly called black noodle seaweed, Gelidiella acerosa) which women traditional gathered during summer for home consumption and for the market. However, nowadays, there are no more buyers for this weed sas source of agar and even households do not gather it regularly for food. The estuary is also home to a variety of shellfish (basongon, etc.) and crabs. Especially during amihan, the waters of Masugod are calm and these food resources are gathered both for home and the market, supplementing whatever the fishers catch during lulls in the behavior of the sea. A particular kind of shellfish called tuway is also found in nipa groves. Bangus, along with other kinds of fish are raised in cages in the estuaries.

The nipa or mangrove palm (Nypa fruticans), is a versatile plant and there are several groves of these in Songcolan. The leaves are used for thatching roofs and woven as wall panels and other purposes. This is one source of supplemental income for the villagers. The sap is collected as fresh drink or fermented as vinegar which can be sold. The fruit, commonly called kaong, is eaten raw or preserved in syrup, a popular ingredient for fruit salads. However, this is one asset which the SSLA members have not tapped for business.

Based on reports from the Philippine Statistics Authority, Aklan’s poverty incidence is the lowest among the provinces in Western Visayas as of 2024, dropping to 4.6 percent in 2023 from 20.2 percent in 2021. It is notable that the same report estimates that 31 families out of 1, 000 are considered poor. The population of Songcolan is 1,228 as of the 2020 census of the PSA. With the situation of the SSLA members, they might be part of those families considered poor. It would be interesting to make studies on the poverty profiles of SSLA members and their families.

To put the food we want on the table

Organized through the efforts of the Episcopal Church Action for Renewal and Empowerment (Episcopal CARE) Foundation, popularly known as E-CARE, the SSLA operates as a self-help group managing resources accessed from E-CARE’s “Receivers to Givers” (R2G) Policy. Under this policy, communities receiving external grants to support their respective projects are enabled to eventually give back and pass on what they received either back to themselves, or to others in need, so that, from being receivers, they, in time, also become givers.

The SSLA envisions itself as a facilitator for raising the quality of life of each member in economic, health, social and spiritual aspects. Towards this end,

- they aim to enhance the capacity of each member in their ability and opportunities towards economic development

- Strengthen the bonds among the members for to share burdens

- To live the “Spirit of Caring and Sharing” as a community

- Develop a strong cooperation towards self-reliance

- Broaden its networking among government organizations and non-government organizations to advance the purposes and goals of SSLA.

SSLA accesses livelihood assistance funds from E-CARE and relends these to its members according to their individual proposals, most of which are to support their livelihoods. As mentioned earlier, this include equipment to enhance their fishing livelihood. Others used it to augment capital for their processing, buy and sell business of fish and seafoods, food vending, and baraca.

Although aimed at poverty alleviation and economic empowerment, recipients have been also using their allocation for emergency cases. The hospitalization of a family member can be devastating to those without, or with, meager savings and one member was so grateful for the proceeds of her loan that allowed her to pay off her husband’s hospital bill. Otherwise she would have been forced to borrow from usurers (Malaking tulong kasi may pera agad sa pag-oospital ng asawa na hindi na mangutang sa mataas na interes). Another allowed her to pay off her high- interest loan and even buy some household needs (Ang kinita ko ay ibinayad sa utang at ibinili ng kailangan sa bahay).

Whatever the members gain from their economic endeavors supported by the micro-lending of SSLA is enough assurance of having food on the table – (Nakatawid kami sa pangangailangan na pagkain sa araw-awa dahil may tiyak na pagkukunan ng pera). Nakatawid is a loaded word. In this context, they are able to bridge one meal to the next. Hearing this story, wasting a morsel of rice seems criminal. This also gives families the freedom to choose what to eat (“nakakain kami ng gusto namin na masarap”, “Nadagdagan ang kita sa araw-araw kaya nakabili kami ng masasarap na pagkain”).

Others are now able to procure household needs little by little (Kahit maliit nakapag-ipon ng gamit sa bahay”), including having the ability to amortize the cost of a washing machine, a big load of laundry her hands. School needs of children and grandchildren are part of the allocation of the meager profit. One member is supporting her granddaughter finish her Information Technology course in college hoping she will continue her business and another is sending her child to college. Truly, investment in education is the best inheritance for a child. The comment of one member sums up what is truly feels to have a little gain to meet basic needs and a little more: “Masaya ang pamilya!” (The family is happy!).

The current members of SSLA are confident in claiming that all of them have improved their economic status since they started their partnership with E-CARE. They can safely say about 80% of them have sustainable livelihoods. While the rest are facing some hurdles, through their group efforts, they are getting there. For Zaidy, the buyers of her fish and seafoods, most from Roxas City, now directly come to her store to get the catch, otherwise, she would have had to leave before sun up to bring her goods to Kalibo about an hour away by ferry crossing the Batan Bay. For Mary Ann, her shell craft business is now a signature product of the barangay. Her creations are displayed at the municipal display center. She and others have participated the municipal trade fairs, and the fact that ECARE visitors bring her crafts to other parts of the country and even abroad brings her much pride.

E-CARE also facilitates training needed to enhance the knowledge, skills and the businesses of the women by linking them with relevant government agencies for needed services, like the Department of Trade and Industry, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), among others. The women had undergone training on several skills and discarded those which are not feasible at this point in time. For instance, they tried into weaving. However, there is no ready market for this so nobody pursued this craft. At one time, they explored the possibility of adding value to their bangus by selling de-boned bangus. However, they laughingly recall that during their training, they said they double- murdered the fish: nothing was left of the fish except the skin. End of the story.

Debt

Debt is the face of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The sea may be bountiful but it is also tricky, unreliable.

Freedom from debt opens the possibility for ensuring food on the table, but also savings. And this has happened. The fact that SSLA is now on its 7th cycle of E-CARE support is testament to this. Each cycle, they paid back the E-CARE including the 1.5% add-on. That add-on is like interest, and that means that for any amount they get from the livelihood assistance SSLA requested from E-CARE, they are able to generate 1.5% of that every month within their agreement period. But that is not the only cash benefit they get because they are able to procure some of their needs and wants.

One may ask – but then where are the savings? Why do they have to go through these several cycles? Is this not the same cycle of debt from usurers?

Happiness to some is being able to have access to food choices. Fish, shellfish, squid, shrimps and lobster – yes, they have those from their catch, and they can have them every day, and yes, they command high price in the market. But no, they are the frontliners who are at the lowest rung of the chain of profits. And no, they are still meeting their basic needs – food, education for the children, maintenance expenses for their livelihoods, daily household expenses. Survival.

What subsistence producers need is simple: resources to pursue their livelihood to supply their daily needs – food, children’s schooling – and allow them to save to further enhance their livelihood, meet emergency needs, allow their children to achieve higher education – and live decently in a sustained manner. To them, time is of the essence: according to Project Officer Romelyn, your competitor is the stomach (tiyan and kalaban). Loans can never compete with food for the family. The cycle of debt is better appreciated when we look at it from the point of view of the least-resourced groups, like these subsistence fishers of Songcolan.

Subsistence fishing is “weather-weather lang”, seasonal according to weather conditions. During the ‘ber’ months, about October until March, it is the amihan season, when the northeast monsoon brings cool dry weather but the seas are rough and usually typhoons originate or hit the southern part of the Philippines where Songcolan is located. Most of the fishers of Songcolan are subsistence fishers and they live day-to-day from their catch. Because of rough seas, fishers do not go out to seas during this season, but they have basic needs to meet. During these lulls in fishing, they can go out but these occasional forays into the sea is not enough to sustain their needs for the whole low season and even for the day.

Just like other subsistence producers, the fishers need a variety of options to sustain their needs all year round. Lucky for these villagers in Songcolan and other villagers living along the estuaries of the province, the islet system provides them food and any extra can be sold, or they can sell their whole catch to procure other needs. The integration of the villages into the market economy and the demands of modern life, e.g., education, health, and even entertainment, however, are accessible only with cash. Even though education is free until Grade 12, health and other needs like transportation, school supplies and projects need cash outlay.

At this time, nature still produces resources within the waters of the sea and estuaries but the villagers have observed slightly declining catch through the years. For subsistence fishers and producers, supplemental income comes from market-driven demands like food, handicrafts, vegetables, among others. A few of these fishers have small landholdings or can rent or use some lots free for farming. These can provide some additional cash income, but actually, they also serve as supplemental food and buffer for lean times.

Actually, the members have savings. One-third of the add-on is given back to the SSLA as part of their capital build-up (CBU) which they use for their internal micro lending activity. The members earn dividends from the proceeds of this relending activity.

In order to have capital for livelihood endeavors, traditionally, people would borrow money from usurers, usually their village mates, commonly known as ‘5-6’ because you borrow 5 pesos and return 6 pesos within a month. This is 20% interest, which translates to 240% in a year.

This is the situation in Batan where Songcolan is located. But this situation persists in many villages in the Philippines. It is for this reason that many poor families become poorer.

From receivers to givers

The Rev. Danilo Bautista, Fr. Dan as he is affectionately named, is a native of Batan. In 2013, he decided to dedicate his last years of active service as a clergy of the Episcopal Church in the Philippines (ECP) in his hometown, which then, had no church in the whole province. As a matter of fact, the ECP only had a presence in Cebu City in the whole of the Visayas islands. “What good is a clergy if he cannot even evangelize his village?” This had been the motivation that drove Fr. Dan to seek for this mission, aside from wanting to retire in his home village. Nobody in Batan has ever heard of the Episcopal Church except Fr. Dan’s family. Although a dominantly Roman Catholic Church community, masses were only held once a month through the years.

Successfully securing a small rent-free building, the Good Shepherd Episcopal Church was consecrated on April 9, 2014 in Ambolong, Batan, serving as the base of the pastoral and evangelical work of Fr. Dan and his family. From that structure, and with curious and individuals hungry for the Word, congregants trickled in until six individuals asked to be received. Together with Fr. Dan’s family, this group served as the foundational congregation of the Good Shepherd

EC achieving the first two Marks of Mission: proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom, and teach and nurture communities with Christian values of love and servant hood.

Being a Batan native and knowing the poverty situation in the community, Fr. Dan saw the need to explore ways of meeting the congregants expressed need for means to meet their basic needs. This was an opportunity to share the E-CARE program to respond to their needs and at the same time fulfill the rest of the 5 Marks of Mission: transform unjust structures of society and challenge violence of every kind, and at the same time, strive to safeguard the integrity of creation and sustain and renew the life of the earth. Normal for any struggling community, the news of the possibility for access to loans attracted more people to attend masses, an unintended result.

The process involved an orientation on the ECP’s Asset Based Community Development Program (ABCD) and Receivers to Givers Policy (R2G) with 53 hopeful participants but after undergoing all the necessary development education and requiring them to form an organization with membership fees and contributing share capital, eventually a core group of 16 were left to form the Seashore Songcolan Livelihood Association. In 2015, this group became the first partner of E-CARE under the R2G policy, receiving their first livelihood assistance, and further registered as a people’s organization in the barangay. The fund was disbursed to members who applied for assistance.

Most of these loans were used to augment the capital of or enhance their existing livelihoods. Others started from scratch like those who started the fabrication of side-cars, and chicken- and hog-raising.

During the 3rd cycle evaluation (this was after a 2-year hiatus) in Feb. 15, 2019, some reported that they used their loans to repay loans obtained at usurious rates, and thus allow them to have some savings from their subsistence fishing and farming. The one who used it to pay medical bills allowed her breathing space to earn for the payment. This is a reminder that being subsistence producers makes it difficult to accumulate enough savings that can be used for emergency and expenses that require immediate settlement and in big amounts. “Magaan sa bulsa” – easy on the pocket – is the term they use to describe the terms required by E-CARE on their loan, 1/3 which goes back to their association as a form of rebate to build up their organizational CBU, and eventually liberate them from borrowing from outside parties.

Savings is not impossible with the R2G E-CARE approach. One member used some of her savings gained from her livelihood to add to the capital of her grandchild’s T-shirt business. Another provides the baon (allowance) of her grandchild, while one is sending her granddaughter to college taking Information Technology source and she sees her as her heiress to her business.

Growing pains

The road to being a giver has not been smooth. The first cycle was finished smoothly with the funds paid back to ECARE and their 1.5% add-on gift duly disbursed and the capital-build up established. This entitled to them for regranting for a bigger amount for the 2nd cycle. Used to dole-outs common among government programs, and the church being usually associated with charity works, some opportunist members absconded on their promissory notes at the end of the 2nd cycle. This forced SSLA to fail their payback obligation and not eligible to access funds for a next cycle. It must be noted that regular meetings were conducted with value formation integrated in the discussions, follow-up were done on persons with delayed payments, among other measures taken to save the face of the organization with E-CARE, as the members claim. The promissory note is written in a language understood by the borrower and discussed fully in meetings before loans are disbursed.

Another problem faced was the failure of a treasurer to remit her collections to E-CARE but she acknowledged that she used it for personal purposes and she signed a promissory note to amortize her payments in instalments. For two years, the SSLA was not able to re-apply for a grant. In the end, not to let the members in good standing suffer from the lapses of others, the association decided to cover the balance of their loan from E-CARE with their CBU. The E-CARE approves the renewal of those who are fully paid, termed as “reconsideration”. This, however, did not free the delinquent members from paying their back loans which until now, are being collected. The SSLA is also willing to go to the extent of filing collection demands with the Katarungang Pambarangay (Barangay Conciliation) to demand collection of these overdue loans as a demonstration of their seriousness in their micro lending initiative and because of the fact that those who refuse to pay back actually have the capacity to do so with their flourishing businesses.

Other corrective measures the SSLA undertook is to clean up their ranks to retain as members only those who uphold their Constitution and By-laws and abide by the policies they have agreed on. Thus, in the end, they are a happy 16 all-women association. With these corrective measures, they

have had good business as proven by their application for a 7th cycle. They continue to hold their monthly meetings, and send their representatives to attend quarterly cluster meetings, where matters of concern are discussed and remedies explored. All these are contributing to strengthened camaraderie, solidarity and friendship. The organizational meetings are often not all business but also venues for sharing, exchanges, and problem-solving sessions.

The SSLA members value E-CARE most for its accessible support, the valuable connections it provides through its network and the connections it facilitates with other helpful entities, and the opportunities for personal and professional growth it offers, which ultimately enables them to actively contribute to their communities.

Church-building

From the one-room chapel building offered for free by a member of the community which served as the home of the Good Shepherd EC for years, a concrete structure with another building serving as the rectory and office now stands on a wide lot that the church owns. Up to date, Good Shepherd is the lone organized Episcopal congregation in Aklan and since its establishment, Fr. Dan and the congregants had a determined drive to build their permanent home through their own resources and capacities under the leadership of the Prime Bishop who was the Bishop-In-Charge of the Visayas Mission Area. Its budget, almost P1.5 million, came from the congregation, contributions of E-CARE staff in the region, ECARE church support fund and largely from the contributions of its various partner outreach communities in the Visayas Mission Area. The construction of the chapel was about to commence when COVID-19 pandemic hit. As part of the R2G community, SSLA contributed to this fund through its add-on remittances to E-CARE. However, the bigger E-CARE community was also involved in this.

With the pandemic forcing the stay-at-home protocol, some members of Good Shepherd as well as its outreach partner households in another barangay organized the Palay Small Enterprises Association to make buri crafts, particularly the bayong which come in various sizes from the leaves of the buri palm tree that grows abundantly in the area. Instead of waiting for relief goods that time, they maximized their home-stay by engaging in various crafts. Who says that the poor were waiting for ayuda? The E-CARE National Office reported that time, taking note of the inspiring productive efforts of Good Shepherd and its outreach communities, the dioceses of the Episcopal Church immediately committed to purchase the bayong from these communities which were sold to their own congregations. This action of the dioceses are an affirmation of the following:

First, by committing to buy the bayong of Aklan, the dioceses expressed full support to the initiative of Good Shepherd Episcopal Church to follow the path of Asset-Based Congregational Development (ABCD) taken by other 30 other local church units which have boldly and successfully built buildings or chapels from own assets and capacities of congregations.

Second, in support of the campaign to end plastics use, the Episcopal Church is promoting the buri-made bayong that is completely biodegradable.

Finally, by supporting the buri-craft of the Aklan communities, the Episcopal Church is providing them income at this time when home-stay has curtailed their farming, fishing and other livelihood activities. Enabling people to earn from their own efforts, as opposed to merely receiving relief goods, enhances their sense of dignity and control over their respective situations. Now, they are constructing a chapel on their own. Indeed, this is a “Story of Hope, The Episcopal Care Way.”

Seeing how the congregation lovingly tend to the church compound -landscaping, cleaning, doing maintenance upkeep and other tasks – and attending the regular Bible studies, evensongs, and masses, even just dropping by, is a manifestation of Matthew 11:28 – “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.”

Water is life

The big blue rain barrel drums at the back of the open gym at the Songcolan Barangay Hall are the rain catchment facility project of E-CARE and SSLA.

Songcolan does not have any fresh-water source. Fresh water is delivered from nearby barangay Ambolong at P100/drum (about 200 liters) or P10/container (about 30 liters). The barangay government installed some pipes but there is no water! Most houses have nipa-thatched roofs and rain water can collected from these cleaning purposes human consumption.

The barangay has a newly constructed open multi-purpose gym and its wide roof was seen by the SSLA as a good source for a rain catchment facility.

Bringing this opportunity to the attention of E-CARE, the latter sought help from one of its development partners, the Anglican Board of Mission-Anglicans in Development (ABM-AID), which extended the needed funds. SSLA coordinated with the barangay government to install this facility with two huge 2000-liter drums. A Memorandum of Agreement was signed by the SSLA and ECARE with the Songcolan Barangay Council. During the visit of a representative of ABM- AID, she saw the need to expand the volume of the facility and donated two more drums of the same capacity, bringing the water holding capacity of the facility to 8,000 liters. Households within the vicinity are served by these drums when there is rain. Water is dispensed from faucets from the drums.

Conveyor pipes were laid out to another sitio of the barangay near the seawall to serve another set of households through a common dispensing pipe.

Sea water has been used for toilets and cleaning but with the construction of the seawall, access to the sea has been limited only to some points. This seawall is still to be finished to cover the entire coastline to stop the coastline from eroding. Originally, Songcolan was far from the sea. It had wide beaches, rice fields, and other productive areas. Through the years, the coastline had been slowly eaten up. However, massive loss of shoreline occurred in 1984 when Typhoon Undang hit the island which led to the loss of rice lands, the beach and homes. This was exacerbated by Typhoon Yolanda in 2013 with its whirlwinds which produced tsunami-like waves. Villagers claim almost 50% of Songcolan has been lost to the sea and thus they welcome the construction of the seawall.

It took E-CARE to demonstrate that a simple rain catchment facility can meet part of the domestic water needs of a community at least cost. This rain catchment project is one of the impactful community development contributions of E-CARE to Songcolan and other water- starved communities, a concrete expression of the 3rd Mark of Mission (respond to human need by loving service) by providing access to vital water services to the underserved. This is a model project that is being explored by other communities and local governments to replicate.

Challenges

At the organizational level, financial opportunism by some members and officers have led to corruption which forced SSLA unable to and had to spend two years to remedy their obligations before they had the face to request for regranting. They visited, encouraged, cajoled these members to pay back. Finally, to remedy, they had to use their CBU to back up the obligations of delinquent members. This pushed the members to refuse to condone bad debts as well-meaning members who sacrifice to meet their responsibilities should not be held hostage to only a very few who refuse to honor their promissory notes.

Members claim about 80% of them have achieved their livelihood goals while others are still facing some hurdles but can still make it in the end. Because of immediate family needs, some individual members faced some challenges in pursuit of their livelihood as they spent some on other needs. The breakout of African Swine Flu (ASF) in almost areas in the country did not spare the hog-raisers of SSLA. This is where they use their internal resources, e.g., in the spirit of sharing is caring, to back-up their members who are facing hurdles in paying back their obligations.

To remedy finance opportunism in the of payments, payments are now encouraged to be paid in Gcash directly to head office and reconciled with treasurer and ECARE Project Officer. Among the fish and seafood traders, they also use Gcash to accept payments from their buyers so they do not have to be keeping big amounts of cash in their homes. To address the trust issues brought about by mismanagement of SSLA officers, the group decided for re-organization in 2022 which trimmed down the members to the present 16. The new set of officers regained the confidence of members to pursue their common goals.

A pestering issue facing Songcolan fishers is that of political boundaries. The sea had always been open access to them as far as they can go and as far as they can remember. However, with the defining of municipal waters now, there are now claims of encroachments when they go to out to sea. However, at their end, their traditional fishing grounds are being encroached by big-time fishers from other jurisdictions, affecting their fish and crab catches. There is a Bantay Dagat (Sea Patrol), a voluntary community team to monitor illegal fishing and other malpractices in the sea, accredited by the BFAR, but they have no police power to make arrests. Villagers claim that sometimes before the team reaches the reported site, the encroachers have already left, insinuating of the collusion of some authorities with the encroachers. These subsistence fishers are frustrated at the lack of success in arresting and prosecuting encroachers seemingly by this inutile agency, but also of the boundary issues between municipalities and the entry of big fishing boats, Fishers usually go around the Sibuyan Sea and know the particular areas therein where fishes and

crustaceans abound at particular times of the year. With these issues, they feel their livelihoods are being threatened.

Community presence: sharing and caring with responsibility

The establishment of SSLA as a community organization is celebrated yearly in April 9th each year. For its 10th anniversary in 2024, the members, together with other E-CARE partners held a motorcade around Batan town. As expression of thanksgiving for a decade of partnership, medical and dental mission was organized by E-CARE and SSLA with the ECP Health Enhancers and Advocates for the Lord (ECP HEAL) which served more than 500 clients from different communities. One of the highlights of the event was the exhibit of different livelihood products displayed by partner communities in their own booths, surely a community fiesta with the festive atmosphere and meaningful fellowship. This was an affirming event for the SSLA who are surely movers for community development. They may be few in number but their activities have positively impacted the community and continue to do so.

In their journey towards empowerment and self-reliance, the members point out the crucial role of the E-CARE staff in their journey. Her being based in the municipality and experience in community organizing as a nurse had been facilitation the resolution of issues they faced, seeking remedies/ response for certain problems that emerged, and networking them with both government entities and civil society. In particular, she pushed for the non-condonation of bad debts as this will be a precedent for new members that organization responsibility must be born equally by all.

One of the objectives of SSLA on social development is to live the spirit of caring and sharing as a community and to build as strong organization towards self-reliance. Towards this end, they have regularly participated in mangrove reforestation, daycare feeding during Songcolan’s annual nutrition month, brigada (school pre-enrolment preparation), foundation day, product exhibits, dental and medical mission of the Aklan-Capiz cluster. They also collect P20 every month for medical and mortuary aid. They once contributed to pay part of a member’s hospital bills and medicines.

The SSLA is an esteemed partner of the barangay. The shell crafts of Maryann showcased in the Batan display center along with other community products is indicative of the community’s recognition of her crafts’ contribution to the municipality’s offerings for tourism and business.